From ancient times, humans have been trying to upgrade living standards from the Stone Age to today’s digital world. Though wellness is the purpose, only a few nations successfully adapted their life towards a healthier life. Japan is a global exemplar of longevity with a life expectancy of 87.14 years for women and 81.09 years for men. Society, culture, and lifestyle have a great impact on their longevity. Their wellness cultures are followed worldwide and show an effective impression on health.

Let’s introduce you to some of their wellness cultures;

Kaizen

Japanese terms kaizen, kai(change), and zen(good) refer to continuous improvements with gradual steps toward growth. Kaizen promotes consistency, not a one-time solution. This philosophy states that tiny but gradual steps ensure growth in a long time.

Kaizen is a mindset, that focuses on business aspects mainly. Though this existed for a long time the Western world was introduced in 1986 through Masaaki Imai’s book called “Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success”. The Toyota Production System had the kaizen principle for the maximum outcome. To gain the outcome they desire, they encourage their employees to identify their areas and improve themselves.

Kaizen is not only a business term. It’s deeper than that. Kaizen consists of two bases: the intention and the actions toward that.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Who do I want to be as a person?

- What steps do I need to take to achieve that version?

Continuous improvement is fruitless without any goal or purpose. Only if we know where we want to see ourselves, then the right direction towards that path is the practice of kaizen. Suppose, you want to be a writer. Every step that you take to be a good writer is a tiny improvement. That’s Kaizen.

How to implement kaizen in daily life?

- The first step is to think about what you want to achieve; can be a small habit or anything.

- Start small; never stop improving yourself even if you feel like nothing is happening.

- Keep track if you’re going in the right direction. But how? What do I want to be? How far I’ve come? What have I learned? what adjustments do I need? Ask these questions.

- The end result will amaze you.

Remember, kaizen is the journey, not the outcome.

Simple way, be intentional and keep moving forward~ Kaizen.

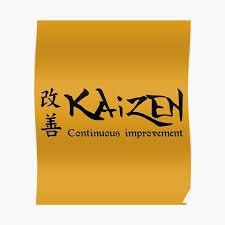

Ikigai

Ikigai- a reason for being is a global term for finding purpose. Populated from Okinawan centenarians, it consists of four fundamental things;

- Doing what we’re good at

- Doing what we love to do

- Doing what the world needs

- Doing what generates money

A popular diagram that is circulated all over the place is somewhat like this:

Ikigai is here the combination of four things: Passion, mission, profession, and vocation. Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life” by Héctor García and Francesc Miralles popularized the term mostly. Western authors have invented this diagram and the above fundamental things.

Okinawan people have found their purpose in life which is one of the causes of their prolonged life. This is also found in the blue zones concept invented by Dan Buettner. One of the elements of power 9: purpose of life.

Related: What is Blue Zones? How do centenarians live a longer life?

What really is Ikigai?

If you really look at the diagram, does it look like a purpose of life or sustainable for all individuals? If we go back to Japan which is the root of ikigai, they never claim to relate money with ikigai. In Japan, ikigai is not used as a self-help term, but rather a common daily used word. It’s a psychology and relative term. Ikigai can be small, can be huge.

Mieko Kamiya is the founder of ikigai psychology. Her book “ikigai-ni-Tsuite” explains what ikigai really means. As a psychiatrist, she worked with individuals who were facing extreme struggles like leprosy patients at Nagashima Aiseien Sanatorium. Her working experience made her realize that no matter what situation an individual is in, their purpose depends on inner perspective rather than external circumstances. Also, Victor Frankl’s ‘man’s search for meaning’ and logotherapy influenced her writing the book in 1965 after World War II.

According to Kamiya ikigai has a dual nature; one is the object that gives the sense of purpose and the other one is the feeling itself “ikigai-kan”(ikigai feeling). There are two questions to ask oneself:

- What is my existence for?

- What is the purpose of my existence? If there is any then am I faithful to it?

Someone might see their pet and say “She is my ikigai”, or look at the family and say “This is my ikigai”. Ikigai doesn’t have to be calculative and generate money. The modern concept of ikigai might create fear and uncertainty, “Is this my ikigai?”, “what if I don’t find any?”. When a person wants to do something that is also their duty, ikigai is most felt then. Harmony between desire and duty.

Ikigai is not permanent, it can change at any point in life. Ikigai is not about the present moment, it’s the future forward. A person looking forward and working to achieve a certain goal is their purpose.

Mieko Kamiya’s ikigai concept is a psychological framework for a person’s finding meaning in life even after a loss. Eddie Jaku considers himself the “ happiest man on earth” after surviving the holocaust. Elie Wiesel earned the Nobel Peace Prize being an advocate for human rights as an Auschwitz survivor. They are the example of ikigai.

Forest Bath(Shinrin Yoku)

Forest bathing, named Shinrin-yoku, was introduced in 1980 by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, making it a relatively modern concept rather than an ancient one.

It’s different from hiking or trekking, as it mainly focuses on mind detoxification. Forest bathing involves strolling through forests and nature with mindful use of the senses—hearing birds chirping, feeling the presence of greenery, and experiencing a breeze different from that of usual places. A mindful walk is the core concept.

As forest bathing has only been around for four decades, there isn’t enough research on its physical well-being effects, but for the mind, it has shown positive impacts, including a reduction in cortisol (the stress hormone) levels.

Benefits?

Stress reduction, enhanced mood, improved blood pressure, and cardiovascular health.

A surprising result from one study found that walking in the forest for four hours twice a day can produce cancer-killing proteins and immune cells. Basically, build a home in the forest!

This resonates with three concepts:

- Yūgen: Encourages mindfulness and appreciation of nature’s quiet, profound beauty—like mist drifting through trees or the sound of rustling leaves.

- Komorebi: The concept of noticing and appreciating small yet enchanting natural details, fostering a sense of wonder and tranquility.

- Wabi-sabi: Embracing imperfection, impermanence, and the beauty of the natural cycle of growth and decay.

Akasawa Natural Recreational Forest is the birthplace of forest bathing. Besides that, Yakushima National Park and Kumano Kodo are two notable locations in Japan for this practice. The chaos of urban life, extreme stress, and deteriorating health have disrupted the peace of human life. With that in mind, this practice was introduced.

➤ Read why the Japanese are trading spas for forests.

Hara Hachi Bu

Hara Hachi Bu is a Japanese term related to lifestyle that means “eat until you’re 80% full”. Inspired by Confucian philosophy japan seems to adopt the secret of healthy eating that is none other than the eating process itself.

Okinawa in Japan holds the world’s most effective and inspiring wellness concept. Not only ikigai, but they have implanted the practice of mindful eating. When the whole world is struggling with diet maintenance, just simply adapting to a healthier approach, they have succeeded in longevity. So,

What exactly is hara hachi bu?

Eating slowly: Our brain needs 20 minutes to process the fullness of the stomach. If we eat slowly then the brain gets the signal of 80% fullness and we can control overeating.

Eating mindfully: Using distractions while eating leads to overeating without realization.

Using smaller plates: Use smaller bowls or plates to prevent taking excess food in plates.

Eating until stomach bloating creates discomfort. Okinawan people are daily using this simple hack. The results are mind-blowing. They have successfully prevented the rate of heart disease, cancer, and stroke which are mostly triggered because of unhealthy diets.

Wabi Sabi

The concept of imperfection, simplicity, and beauty in flaws. It bears a long history and deeper meaning than looking the surfaces. Though wabi-sabi is considered a Japanese term, its origin is in China. From Zen Buddhism in China to Japan the roots go deeper.

History of Wabi-Sabi:

During the 15th century, Chinese tea culture and its lavish design heavily influenced Japanese tea culture. Chinese tea culture was more of a prestigious gathering and a symbol of luxury. When the Zen philosophy entered Japan, with its simplicity, mindfulness, and humility, tea culture also took a different turn. It became a way of meditation and spiritual practice.

Murata Juko is considered the father of Wabi-cha, a Zen monk and tea master. He emphasized that Japanese tea culture should embrace its own unique simplicity instead of copying luxury. Simple utensils and pottery made of bamboo shifted the focus from materials to spiritual reflection. After Murata Juko, his student Takeno Joo carried the culture forward and actively promoted the beauty of imperfection, respect, and purity through the tea ceremony.

Sen no Rikyu fully integrated the philosophy of Wabi-Sabi from Wabi-cha. A story is told that he went to learn about the tea ceremony from Takeno Joo and was tested. Takeno Joo told him to take care of the garden, so he cleaned it thoroughly. Before he could report that the task was done, cherry blossom petals fell from a sakura tree onto the ground. At that moment, he realized the beauty of the little mess created in the garden, which was none other than Wabi-Sabi.

Rikyu favored tea utensils that were asymmetric and rustic. They were intentionally made in such a way that represented natural harmony, embracing imperfection and mindfulness. That’s how Wabi-Sabi took a permanent place in Japanese wellness culture.

What is Wabi-Sabi?

Wabi is embracing the beauty in simplicity—to see something not in a materialistic way but from the heart. Sabi is the natural flow of time that comes with age, decay, and growth.

When you look at an elderly person, what do their wrinkles say to you? The wrinkles represent that they have lived through happiness and struggle. They have experienced life itself. Everything that is decaying has its own story. Everything comes, lives, and goes away. Nature has its own limited purpose and beauty.

The asymmetry and flaws seen everywhere are what make our surroundings livable. That’s why there is no such thing as ‘perfection.’ Nothing and no one can be perfect. Rather than running after perfection, why not accept the natural flow of life?

Wabi-Sabi Teaches Us:

- Imperfection is beauty.

- Embrace the flaws.

- Aging and decaying are symbols of a journey.

- Simplicity has its own elegance.

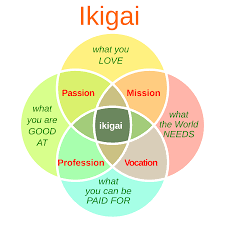

Kintsugi

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken things. It is a part of Wabi-Sabi—a way of fixing what is broken or flawed. Let me tell you the story behind it first:

Ashikaga Yoshimasa was the eighth shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate during the Muromachi period. Ashikaga was fond of art and culture. Being an admirer of art, the tea ceremony was one of his favorites. He owned an expensive Chinese tea bowl. One day, the bowl broke accidentally, and he became distressed over it. He sent the broken bowl back to China, hoping they would fix it. They did fix the bowl within their capability using metal staples, but it looked hideous.

Ashikaga then contacted Japanese craftsmen to find a better solution. Interestingly, the craftsmen found a way. They used ‘urushi lacquer’—an adhesive from tree sap—and concealed the cracks with gold powder. The golden lines made the bowl even more beautiful than the original version. Thus, the art of Kintsugi was born.

What Does Kintsugi Teach Us?

The story of Ashikaga and the broken bowl can be a symbol of life. Compare the broken bowl with loss in life. Loss doesn’t mean the end; it can be the start of something beautiful. Loss can be the push toward a greater achievement. In moments of despair, we might feel like nothing is working, as if darkness is taking over. But when the sky clears, we can move forward with more clarity.

Kintsugi teaches us that flaws are not ugly, and being broken is not the end. How we perceive things shapes our outcome. It teaches us resilience—enjoying the moment with patience. Kintsugi is the artistic way of presenting the impermanence of the universe. Nothing lasts; everything decays. Enjoy life while you still can.

Yuima-ru

In Okinawan culture, Yuima-ru means “working together.” Yuima-ru is not just a philosophical concept; rather, it has been integrated into their daily lives. They deeply value community connections. As people age, they deal with struggles—aging, losing loved ones, and loneliness. But with a supportive community, these struggles become manageable.

Okinawan elders are supported by their people. Gateball is a game similar to croquet, designed for social and strategic engagement among older adults.

They have Moai, a system where they support each other financially in times of need. Everyone contributes 10,000 yen, and the money is given to the one in need. Their strong bond has maintained this culture without any abuse, dispute, or misuse of the system.

A strong network boosts their confidence because they know they have each other’s support. Yuima-ru is about cooperation and mutual help. Okinawans are reputed for their longevity, and one of the key factors contributing to this is their Yuima-ru culture.

Tariki and Jiriki

Japanese religion has two modes: one is relying on one’s own power, and the other is relying on another’s power. Jiriki is self-power—lifting oneself through one’s own effort—while Tariki is relying on a god’s power and calling for help.

Jiriki is often compared to the “way of the monkey.” When a mother monkey moves, her baby must cling to her using its own strength. In contrast, Tariki is compared to the “way of the cat.” A mother cat carries her baby in her mouth as she moves.

In Japanese Buddhism, the concepts are contradictory. Jiriki is extensively integrated into Zen Buddhism, where mindfulness, meditation, and martial arts such as Kendo, Judo, and Aikido are practiced. Jiriki Seitai is a Japanese self-healing treatment. It’s not just stretching but a process of release where you are both the therapist and the patient. Through exploring the inner self and unlocking mental barriers, healing begins.

Tariki in Japanese Buddhism emphasizes faith and compassion toward Amida Buddha. Relying on prayer and divine power is the core belief of Tariki.

Shukanka

Shukanka is a Japanese term that refers to habit formation. It shares a similar concept with Kaizen, but Shukanka specifically focuses on building habits. Habit formation is not an exaggerated approach to life; rather, it emphasizes the importance of simple daily tasks. Reading habits, healthy eating, exercise—any repetitive activity that requires consistency—are part of Shukanka.

How Can We Practice Shukanka?

The easiest way is to take small steps toward any particular activity. Suppose you want to build an exercise habit. Start with just five minutes a day, then gradually increase the time while maintaining consistency and accountability.

Shukanka is a great concept to integrate into daily life. It increases one’s sense of accountability and responsibility toward tasks and routines. Building a simple, healthy habit might seem small, but it has a huge impact on overall life.

These rituals are not only a guide to a healthier life but enrich cultural lessons. Integrate the lessons into daily life by practicing kaizen ~ consistent progress.